Hauling passengers on a 40-foot city bus has never been glamorous. But Ryan Timlin could at least see the potential back in 2006, when he was earning nearly minimum wage at a St. Paul hardware store and hungry for a change. A friend who worked at Metro Transit, the public transportation agency for the Twin Cities, convinced him that driving buses meant good pay and a stable future. So Timlin donned the striped Metro uniform and got behind the wheel, ferrying passengers around Minneapolis and St. Paul every day for 11 years.

Timlin, now 38, recently settled into a new role as president of his local Amalgamated Transit Union chapter. He has no regrets about his career. But if he was younger and searching for a new job today, he isn’t sure he’d choose the bus route. “I loved that job, even with all its baggage,” he said over the phone last week. “But it’s hard to say that I would do it again, because of how it’s gotten.”

How has it gotten? By many accounts, driving a city bus is a worse paying, more arduous, and more dangerous occupation than it once was. Yet many more workers are needed, badly, for a job that few seem eager to do. There’s an industry-wide labor shortage, and it is affecting passengers by straining service.

You don’t have to look far to find this problem. Across the country, transit agencies are working overtime to recruit more bus drivers. King County Metro in Seattle, Washington, needs about 100 more people to make up their operator gap. Ray Greaves, the New Jersey State ATU chair, believes New Jersey transit needs at least 200 more bus operators across the state. As of last December, Regional Transit Denver was short 127 bus drivers. L.A. County Metro, which operates the second-largest bus system in the country, is hustling to fill shifts.

Riders may be feeling its effects, too. A 6 percent cut in bus service by the Toledo Area Regional Transit Authority in Ohio earlier this year—the second year in a row—was attributed in large part to their driver shortage and growing overtime expenses. In Gainesville, Florida, cutbacks that hit 17 routes—setting back arrival times as much as 15 to 35 minutes—were linked to a lack of bodies behind the wheel. Louisville’s 40 operator vacancies were resulting in delays on about 10 routes every day earlier this year. The shortage is plaguing rural and suburban systems, too: The Cooperative Alliance for Seacoast Transit in New Hampshire is short at least 25 percent of the workforce it needs to cover its timetable.

Why doesn’t anyone want to drive the bus? Once upon a time, it was considered an honorable and desirable gig—a stable union job with a good middle-class salary, a public pension, and at least some cultural recognition for the contributions it made to society, if bus-driving everyman heroes like Ralph Kramden of “The Honeymooners” were to be believed. Like many public sector jobs, it provided a reliable foothold on the ladder of social ascension. Even if you didn’t have a college degree, being a city bus driver meant you could buy a house, feed your family, take a vacation, save for your child’s college tuition. And relative to other transportation jobs, transit is still more inclusive of women and people of color.

But public sector jobs of all kinds have declined in pay as collective bargaining continues to be eroded. Bloated MTA salaries may be a punchline in New York City, but not so in other towns. The median hourly wage for a municipal bus driver in the U.S. is $19.61,according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. That’s above-average pay, and seasoned employees can make double. But as with all kinds of low- and middle-income jobs, driver wages have barely kept up with the rate of inflation over the past decade. Entry-level paychecks tend to be much smaller, which can pose a barrier to many young workers, especially with the fee required to earn the requisite commercial driver’s license.

But public sector jobs of all kinds have declined in pay as collective bargaining continues to be eroded. Bloated MTA salaries may be a punchline in New York City, but not so in other towns. The median hourly wage for a municipal bus driver in the U.S. is $19.61,according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. That’s above-average pay, and seasoned employees can make double. But as with all kinds of low- and middle-income jobs, driver wages have barely kept up with the rate of inflation over the past decade. Entry-level paychecks tend to be much smaller, which can pose a barrier to many young workers, especially with the fee required to earn the requisite commercial driver’s license.

Sustained funding cuts that began during the recession have further challenged transit agencies to keep pay competitive. Less funding also translates into diminished routes and reduced frequencies, which seem to be the most important factors driving down bus ridership around the U.S. Welcome to the transit death spiral: fewer riders, lower revenues, lighter paychecks. “We have drivers who are homeless in this country,” Larry Hanley, the president of ATU International, the largest labor union representing transit workers in the U.S., said. “In the Google area of California, the pay is so suppressed that we have drivers who are sleeping in their buses.”

Hanley was referring to a policy in Santa Clara Valley Transportation Authority, which for 20 years has permitted employees who live more than 50 miles away to sleep on trailers parked on its property. Some drivers also choose to snooze in their cars on nearby streets, according to the San Francisco Chronicle. News broke this week that VTA, which faces a $26.4 million budget gap for the coming fiscal year, is phasing out its official sleep-permitting policy.* Operators there aren’t sure what they’re going to do.

Labor shortages are a barrier even for cities that look healthy from a transit perspective. Until King County Metro in Seattle—a rare example of 21st-century bus ridership success—can fill its 100-person driver gap, it won’t be able to fill rising demand for more service, one county transportation planner told me in March. Back in Minneapolis and St. Paul, which have been praised for increasing bus and rail service to meet a growing population, “we do not see that number [of bus operators] moving the right direction without any additional programming or assistance,” Aaron Koski, the head of Metro Transit's workforce development department, told MPR News in May. A system expansion “will put more pressure on the need to have a full complement of operators to deliver service.”

There were always times when Metro Transit struggled to meet the demands of the system, like during state fairs or holidays, Timlin told me. “If there’s no one there, the bus just gets cut,” he said. Part-time drivers are running in short supply; pushing overtime too often burns out full-time workers.

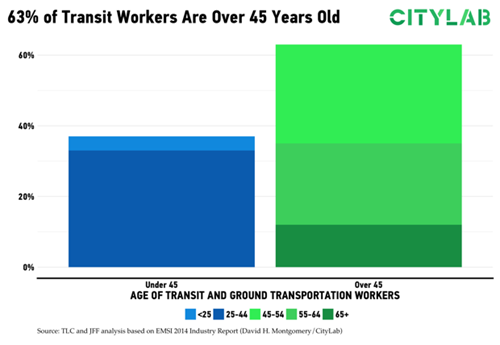

Virtually all of the old transportation trades, private and public, are facing hiring struggles, from school bus systems to trucking industries. A “silver tsunami” retirement wave is hitting them hard, and ground transit—which includes city buses and intercity coaches—has the highest percentage of workers over the age of 55 (35 percent) compared to the trucking, air, rail, and maritime transportation sectors. A staggering 63 percent of transit workers are over the age of 45. While trucking has the greatest projected future labor needs, buses are hardly dying out, contrary to what you might read about Uber and Lyft killing transit. Nearly 200,000 transit and intercity coach driving jobs are estimated to open up by 2022, according to a 2015 joint analysis of BLS data by the U.S. Departments of Transportation, Labor, and Education. And nearly 72 percent of the current operator workforce is set to exit by that year.

Virtually all of the old transportation trades, private and public, are facing hiring struggles, from school bus systems to trucking industries. A “silver tsunami” retirement wave is hitting them hard, and ground transit—which includes city buses and intercity coaches—has the highest percentage of workers over the age of 55 (35 percent) compared to the trucking, air, rail, and maritime transportation sectors. A staggering 63 percent of transit workers are over the age of 45. While trucking has the greatest projected future labor needs, buses are hardly dying out, contrary to what you might read about Uber and Lyft killing transit. Nearly 200,000 transit and intercity coach driving jobs are estimated to open up by 2022, according to a 2015 joint analysis of BLS data by the U.S. Departments of Transportation, Labor, and Education. And nearly 72 percent of the current operator workforce is set to exit by that year.

The transportation trade facing the most existential angst right now is probably taxi driving. Uber, Lyft, and other ride-hailing services have blown up that industry’s rigid, medallion-based business model, leading to plummeting earnings (and a wave of suicides among New York cabbies). For better or worse, new players dramatically lowered the barrier to entry for workers who wanted to plug in and drive. Indeed, the allure of ride-hailing gig work may be siphoning off would-be bus drivers, some of the union and transit agency leaders I spoke with suggested. Driving for services like Amazon Flex may be another draw.

But there’s a distinction between the bus and taxi labor crises: Buses themselves aren’t critically endangered, as the demand for operator jobs right now proves. Bus driving, however—at least as the job has long been described—might be, if the profession doesn’t undergo a radical makeover.

About CityLab

.png) CityLab is dedicated to the people who are creating the cities of the future—and those who want to live there. Through sharp analysis, original reporting, and visual storytelling, our coverage focuses on the biggest ideas and most pressing issues facing the world’s metro areas and neighborhoods.

CityLab is dedicated to the people who are creating the cities of the future—and those who want to live there. Through sharp analysis, original reporting, and visual storytelling, our coverage focuses on the biggest ideas and most pressing issues facing the world’s metro areas and neighborhoods.

Comments

There are no comments yet for this item

Join the discussion